ZIA SUNTA

The story of a beloved auntie, a loving wife and a commissioned piece of art.

My incredible wife, Ljudi, commissioned the best birthday gift I didn’t know I wanted, by artist Tanja Hollander.

My Zia (aunt) Sunta, my grandmother’s sister—was the oldest in a lineage of women that ends with me. Through three generations, she was selflessly dedicated to taking care of us. She was our pillar, the grandmother elephant, the oldest tree in the forest.

When I lost Zia Sunta, I kept some of her belongings in a box. Unbeknownst to me, my wife opened the box and sent the contents to Tanja. I am almost certain that those objects traveled more in one round trip—from my house in London to Tanja’s studio in Maine—than Zia Sunta ever traveled in her life.

After touring the world for the epic project Are you really my friend?, Tanja had developed a sixth sense for creating memories from objects gathered during her journey, dematerializing them and rendering them eternal with the light of a scanner and composed arrangements. Many of these artworks were exhibited at MASS MoCA during her solo show in 2017.

Recently, Tanja started asking people to send their personal ephemera for her to scan to create artworks from their memories. Ljudi and I witnessed this process in early 2020 in San Juan Island, Washington. I loved Tanja's new project, I saw it as the perfect natural evolution after Are you really my friend?,

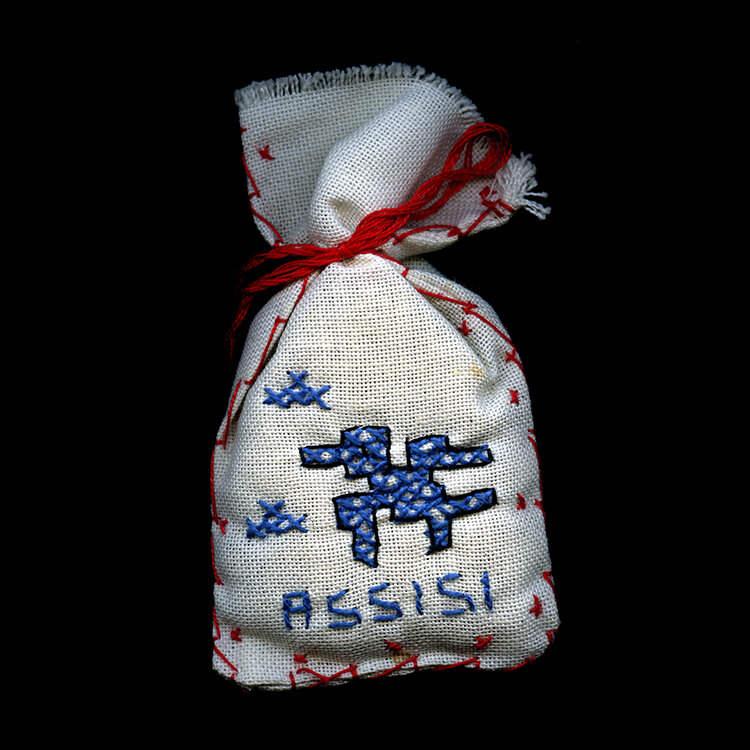

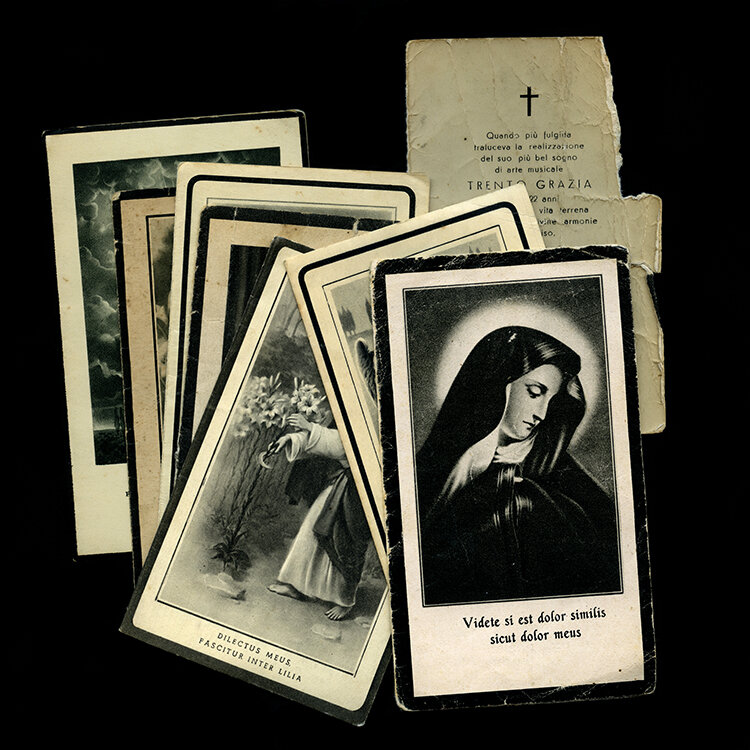

Zia Sunta and my grandma had three brothers who fought in WWII. One was captured in Croatia and released years later; another was lost at sea; and the third joined the Partisans to fight the Fascists in Italy. My aunt was sixteen when their parents died, and she began taking care of the family, a fate that never ended. She learned how to cook, mend clothes, and sell coal to get some food on the table.

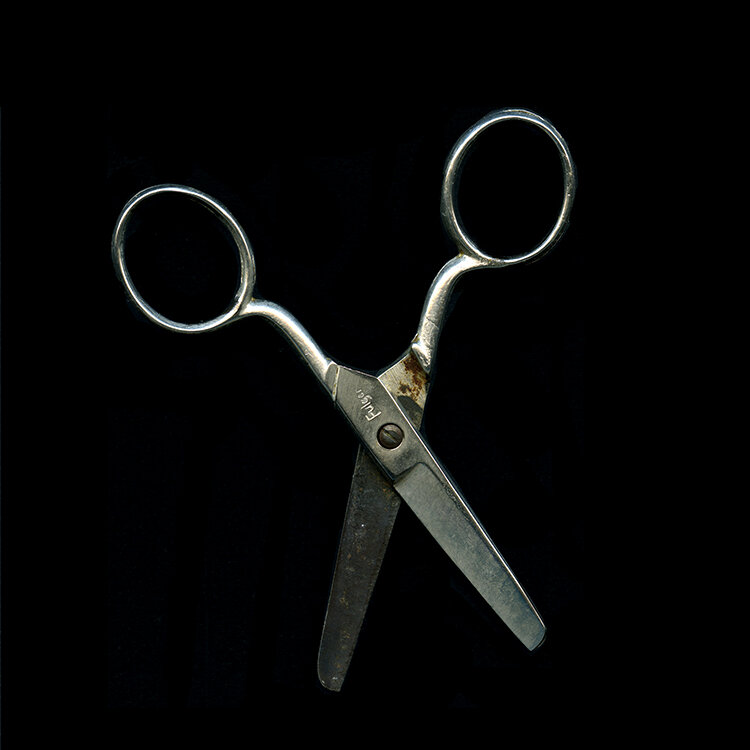

When my grandparents married, Zia Sunta went to live with them, caring for their four daughters. After my brothers, cousins, and I were born, she kept it up: cooking, reading, teaching us how to sew and take care of ourselves. In the pristine, unspoiled dialect of our Italian village, she would tell us, Fioli, ‘sté ‘tènti! (“Kids, don’t get yourselves hurt”). She kept a pair of rounded-tip scissors in her dressing gown that, for some reason, were all I ever wanted. One day she told me, “The day I’ll be gone, you’ll have the scissors.”

For years she rarely left the house, other than for ceremonial occasions and to vote. Italy granted women the right to vote in 1945, and she first voted in the 1946 referendum that ended the monarchy. Voting was a hard-earned right for her, and she proudly never missed an election.

Zia Sunta was The Memory of my family. You could ask her any question with regard to anyone in our extended family and she would know everything: dates, connections, every little detail. On top of that, she had a thorough map of each person’s taste in food and would often remind us what we liked and disliked.

One thing I am not sure if Zia Sunta was aware of the nature of my relationship with Ljudi. When we originally decided to get married, I said that I didn’t want the wedding to happen while Zia Sunta was alive. Making that decision tore me apart and still haunts me today. It’s a common conundrum in our LGBTQ+ community: do you bear the weight of lying to someone you love or do you risk telling them the truth, accepting that you could forever lose them? I didn’t need Zia Sunta to understand my sexuality. I knew she loved me. At the same time, I was keeping her away from a true and fundamental part of my identity. I guess that’s what comes with conservative families and being outed traumatically. Ljudi and I got married in 2018, two years after my aunt’s death.

Tanja and Ljudi worked at creating an artwork out of Zia Sunta’s box of ephemera, with Ljudi recounting the stories behind each object and Tanja interpreting them. When I opened the gift (a print of Zia Sunta’s belongings), I was speechless, then in tears. I felt as if I was unearthing a now eternal memory of someone long gone, who was finally going to be forever with me. By decontextualizing the objects and laying them on a dark background, Tanja made the ephemera look like eternally floating archeological finds that are surfacing from the bottom of the ocean, intercepted by the light of the scanner. The grid system gently applies a sense of democracy. The scale is 1:1 for the two objects that I care about the most: the scissors she’d always promised I’d have, and the watch, my last gift to her when she was losing track of time at the hospital. I love how the dressing gown on the left—her absolute favorite “leisure” garment—is placed opposite a piece of her ceremonial dress, which she wore when my grandparents got married. She was buried wearing the rest of that set.

I felt so seen; first by my wife, who has the biggest heart on earth and a sublime taste for gifts, and then by an incredible artist who has cheated time for me and Zia Sunta.

The last time I saw Zia Sunta she thanked me, saying that she never realized she was loved so much. Here it is, another example of her being so incredibly humble and selfless. Of course she was loved; she was our family, our everything, our eldest. When I think of her, I think of elephants.

Every once in a while, I would open the box just to remind myself of what is in there. Ultimately, we are seeking the memory and not the object in and of itself. The object is the key to a drawer inside us. Now I have access to my drawer, I no longer need the key.

Check out Tanja’s work, she has been commissioned by families, friends, couples, individuals. I have seen her scan all sorts of things.

-Luna Cardilli, 2020

Purchase your own family commission.

More information on the Ephemera Project.